The United Nations human-rights agency said China’s government may have committed crimes against humanity in its treatment of ethnic Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, in a report that broadly supports critical findings by Western governments, human-rights groups and media detailing mass abuses in the region.

In a long-awaited report issued Wednesday, the U.N. agency assessed that serious human rights violations have been committed in the course of Chinese government’s efforts to combat terrorism and extremism. The agency quoted what it described as former detainees of internment camps in Xinjiang with credible accounts of torture and other forms of inhuman treatment between 2017 and 2019, including some instances of sexual violence. The U.N. body said detainees had no form of redress.

The 46-page report characterized what it termed arbitrary detentions in Xinjiang as stemming from a system of anti terrorism laws in China “that is deeply problematic from the perspective of international human rights norms and standards,” noting that detainees were apparently targeted for their religious practices and other vague criteria.

The report also cited descriptions of possible forced labor associated with internment camps, including labor and employment schemes for the purported purposes of poverty alleviation and the prevention of extremism. It said the extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention of members of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim groups “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.”

The U.N. body urged Chinese authorities to take “prompt steps to release all individuals arbitrarily deprived of their liberty” in Xinjiang and to undertake “a full review of the legal framework governing national security, counter terrorism and minority rights,” as well comply with international conventions on forced labor.

The findings largely support allegations in recent years from Western officials, rights watchdogs and news organizations that have triggered widespread condemnation of Beijing and support for the Uyghur cause.

The U.S. has alleged genocide in Xinjiang—the U.N. report doesn’t contain the word—and sanctioned Chinese officials it blames for the alleged human-rights abuses. The U.S. has also banned imports of most products produced in Xinjiang, such as cotton.

The U.N. assessment emerged in the face of strong objections from the Chinese government, which reviewed a copy ahead of publication. Beijing’s response appeared in the report’s annex, which contained a three-page statement issued by China’s Permanent Mission to the U.N. in Geneva, as well as a lengthy document produced by the Xinjiang regional government—stretching more than 120 pages—that defended Chinese policies there.

The mission’s statement said China firmly opposed the release of the report and said it was based on disinformation by anti-China forces. China argues that its Xinjiang policies are aimed at defusing risks of terrorism and to alleviate poverty, and that critics ignore improvements in living standards delivered by the government.

The U.N. report was released just minutes before midnight in Geneva, where the rights agency is based, on the final day of the four-year term served by the departing U.N. high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet.

Since taking office in September 2018, Ms. Bachelet has led an effort by the U.N. agency to assess claims of rampant abuses in Xinjiang. She pledged to issue the findings in a report, which became the subject of contention as U.S. officials and rights watchdogs accused the U.N. of delaying its release, while Beijing lobbied against its publication.

Human-rights groups applauded the report’s release, expressing hope it will generate a strong response from U.N. member states and international corporations.

“The High Commissioner’s damning findings explain why the Chinese government fought tooth and nail to prevent the publication of her Xinjiang report, which lays bare China’s sweeping rights abuses,” Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch, said in a statement.

“This is a game-changer for the international response to the Uyghur crisis,” Uyghur Human Rights Project Executive Director Omer Kanat said in a statement.

Among those held in Xinjiang is Uyghur intellectual Ilham Tohti who in 2014 was jailed for life on charges of separatism; on Wednesday, his U.S.-based daughter Jewher Ilham said she welcomed the U.N. report but that it brings her “little comfort” because she believes her father was jailed on charges he didn’t deserve and that she has had no contact with him for nine years.

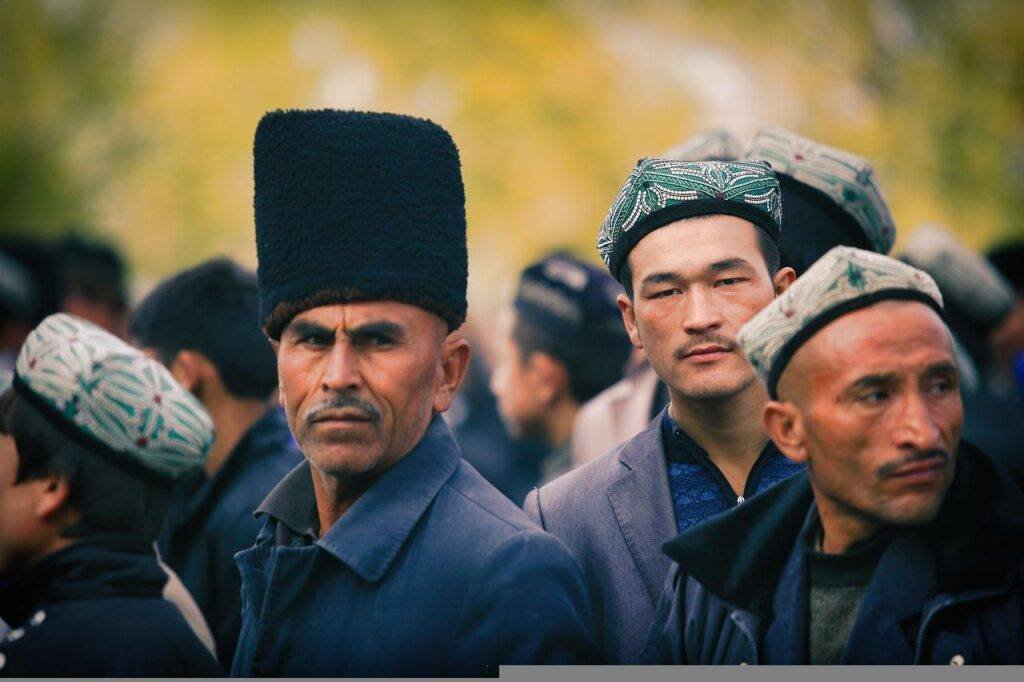

Xinjiang, a swath of desert and mountains abutting Central Asia, is home to roughly 14 million Turkic-speaking Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities. Rights activists and scholars estimate that Chinese authorities in the region have funneled more than a million people through internment camps, while implementing political indoctrination, forced labor, family separations, strict birth controls and restrictions on religious practices that target Uyghur and other Muslim communities.

The U.S. State Department and lawmakers in Canada, the U.K., and France have argued that China’s actions in Xinjiang amount to a form of genocide. An independent, U.K.-based panel of lawyers, academics and activists came to the same conclusion in December following a yearlong investigation.

Agricultural and industrial supply chains involving Xinjiang are under new scrutiny because the region is a major producer of cotton, tomatoes and chemicals used in high-technology applications such as solar cells. Concerns about Xinjiang were a basis for the Biden administration and some other Western governments to diplomatically boycott this year’s winter Olympics in Beijing.

Beijing has denied committing rights violations in Xinjiang, calling genocide allegations “the lie of the century.” Chinese leader Xi Jinping has said that the party’s policies in Xinjiang are “completely correct,” and that they helped restore stability to a region once racked by ethnic violence and deadly attacks against symbols of Beijing’s authority. He visited the region in July.

Critical findings of China from the U.N. contrast with Beijing’s growing rhetorical and financial support for the world body, which Mr. Xi has said better represents world opinion than organizations like the Group of Seven that it says are controlled by Washington.

In its Wednesday report, Ms. Bachelet’s office didn’t estimate how many people were held in Xinjiang but referred to a separate 2018 U.N. agency estimate that detainees numbered in the tens of thousands to over a million. It said Beijing responded to those estimates at the time by saying that detainees, which it says are undergoing “re-education,” come and go so total figures aren’t available.

Drafting of the report spanned years, during which rights watchdogs accused the U.N. rights agency of delaying its release, particularly after Ms. Bachelet said in September 2021 that her office was “finalizing” the document. The agency continued working on the report as it arranged for Ms. Bachelet to travel to the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou and Xinjiang in late May—the first China visit by a U.N. high commissioner for human rights since 2005, and a trip that drew criticism from Western officials and rights activists for allegedly playing into Beijing’s narratives on its rights record.

Two weeks after her China trip, Ms. Bachelet said she wouldn’t seek a second term as high commissioner, citing personal reasons. The former Chilean president, who turns 71 in September, also pledged to release the report before her four-year term expired. The U.N. has yet to announce Ms. Bachelet’s successor.

Chinese officials lobbied heavily to block the report’s release. In July, Beijing said nearly 1,000 nongovernmental organizations in China and elsewhere signed a letter saying the report would be used as “an excuse to interfere in China’s internal affairs.” Ms. Bachelet said last week that she also received a letter signed by about 40 or so countries urging her not to issue the report.

“I have been under tremendous pressure, to publish or not to publish, but I will not publish or withhold publication due to any such pressure. I can assure you of that,” Ms. Bachelet told reporters. “Our work is guided by human-rights methodology and the facts on the ground, and objective legal analysis.”

The assessment issued by Ms. Bachelet’s office came on the heels of a separate set of findings from a U.N. special rapporteur on contemporary slavery, who wrote a report—dated July—saying that he found it “reasonable to conclude” that forced labor was taking place in Xinjiang.

The rapporteur, legal scholar Tomoya Obokata, cited an independent assessment of information that included academic research, victims’ testimonies and government accounts. A Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman rejected Mr. Obokata’s claims and accused him of trying to “malignly smear and denigrate China.”

Subscribe to Updates

Get the Latest Geo-Political, Defence & Military News From The Defence Times